WAC HISTORY - IN TEN EASY STEPS

1. The WAAC came before the WAC. On May 14, 1942, the U.S. Congress signed a compromise bill to create the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps, and President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed it the following day. The Congresswoman who introduced the bill, Edith Nourse Rogers, wanted women to serve in the Army rather than with the Army, but she knew that wouldn't pass due to the resistance of, among others, Congress and the War Department.

2. The WAAC got off to a rough start. WAACs did not receive the same pay, rank, or benefits as male soldiers—a major problem since women in the Marines and the Navy were integrated from the beginning. Women signed up anyway and proved the merit of the WAAC “like the proverbial American success story,” according to The Washington Post in July 1943. Success, however, could not stop the “slander campaign” of gossip, jokes, slander, and obscenity against all women in the Army.

3. The patience of Congresswoman Rogers paid off. On July 1, 1943, President Franklin Roosevelt signed a compromise bill passed by Congress to establish the Women’s Army Corps (WAC) and gave women full military status. Members of the WAAC were given 90 days to either join the WAC or be discharged. The WAAC ceased to exist on September 30, 1943.

4. Over 150,000 women served in the WAAC/WAC during World War II. The WAC never met its enlistment goals due to social pressure—both inside and outside the Army—against women who contemplated enlistment. Although eventually 406 non-combat jobs were opened to WACs, the women came to realize that as long as they were excluded from combat, they were not full-fledged members of the Army.

5. World War II ended in 1945 and, given the reduction in the WAC over the next few years, it almost seemed like the WAC did, too. By June 1948, only about 5,000 WACs were on active duty.

6. The hard-won Women’s Armed Service Integration Act of 1948 granted women permanent status, but not equal status, in the Regular and Reserve forces of the Army, Navy, and Marine Corps, as well as the newly created Air Force.

7. Korean War (1950-1953). The WAC increased in size during the Korean War to a high of approximately 11,900 women, but never met its enlistment goals. After the Korean War ended, the WAC decreased again. A small group of dedicated WACs kept the Corps going through the post war 1950s and 60s, a period when the range of non-combat jobs open to women kept shrinking.

|

March 1953. Major General Palmer, G-3, Army Field Forces, Fort Monroe, Virginia, confers with WAC officers from WAC Center and WAC School (left to right Major Allen, Major Lynch, and Lieutenant Colonel Sullivan) regarding the move of the Center and the School from Fort Lee, Virginia, to Fort McClellan, Alabama. (Photo: The Women’s Army Corps, 1945-1978, p.147)

|

8. The Vietnam War (1965-1975). As the draft came to an end in June 1973 and the All-Volunteer Force became a reality, the need for “manpower” began to increase the number of women in the Army and to expand their role.

9. WAC Expansion (1972-1978). The WAC grew four-fold in strength as changes in law, regulation, and policy offered women more opportunities. Men and women sometimes found adjustment challenging in an Army unprepared for the new WAC pioneers. Approximately 53,000 women were serving in the WAC on October 20, 1978, when Public Law 95-584 abolished the Women’s Army Corps and its members were integrated into the Regular Army.

10. The WAC existed in an era when the battle for survival and acceptance of women in the Army took priority over the battle for equality. The real questions were never can women serve in the Army and in combat (yes, they are capable), but rather should they.

"WAC History in Ten Easy Steps,” compiled by Lynne Schall from the following sources:

- Vicki L. Friedl, Women in the United States Military, 1901-1995: A Research Guide and Annotated Bibliography, Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut, 1996.

- Jeanne Holm, Women in the Military: An Unfinished Revolution (revised edition), Presidio Press, Novato, California, 1992.

- Bettie J. Morden, The Women’s Army Corps, 1945-1978, Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, United States Army, Washington, D.C., 1990.

- Mattie E. Treadwell, The Women’s Army Corps, Special Studies,The U.S. Army in World War II, Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army, Washington, D.C., 1954.

WAC HISTORY - THE CLASSICS

For a more in-depth discovery of WAC history, check out these nonfiction classics:

For a more in-depth discovery of WAC history, check out these nonfiction classics:

|

1954

|

Mattie E. Treadwell, Lieutenant Colonel, U.S. Army, The Women's Army Corps, Special Studies, The U.S. Army in World War II, Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army, Washington, D.C. 1954, 1995. 841 pages.

|

1990

|

Bettie J. Morden, Colonel, U.S. Army, The Women's Army Corps, 1945-1978, Washington, D.C.: Center for Military History, 1990, 1992. 543 pages.

|

|

1992

|

Jeanne Holm, Maj. Gen., USAF, (Ret.), Women in the Military: An Unfinished Revolution, Novato, California, Presidio Press, 1982, 1992 (revised edition).

560 pages. Major General Holm's book addresses women in the Army, Navy, Air Force, Marines, and Coast Guard. |

More Resources

|

1996

|

Vicki L. Friedl, Women in the United States Military 1901-1995: A Research Guide and Annotated Bibliography, Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut, and London, 1996.

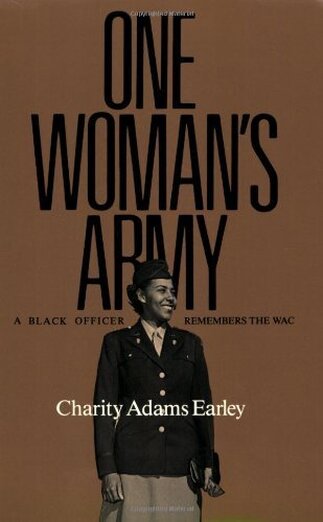

In Table 3 of her book, Friedl tallied the number of personal memoirs/biographies of individual women who served in the armed forces from World War I through the Persian Gulf War. She found seventy-one. Fifty-eight of the seventy-one were written by women who served in World War II. Friedl recommends the excellent memoir by Charity Adams Earley, One Woman's Army: A Black Officer Remembers the WAC, as a guide for other women documenting their service. |

|

2023

|

Charity Adams (1918-2002), was the highest-ranking Black woman officer in World War II. Effective April 27, 2023, her name became part of the re-designation of Fort Lee, Virginia, to Fort Gregg-Adams.

Charity Adams enlisted in 1942 and rose through the ranks to become a lieutenant colonel. Through her service in the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps and the Women's Army Corps, (1942-1946), she became best known as the commanding officer of the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion. She married Stanley A. Earley, Jr. in 1949 and ultimately settled in Ohio where they raised two children.

The significant accomplishments of Lieutenant Colonel Charity Adams in U.S. Army history led the Naming Commission of the U.S. Congress to recommend her to be honored along with Lieutenant General Arthur J. Gregg in the re-naming of Fort Lee, Virginia, to Fort Gregg-Adams. Sources: 1. "Biographies - Charity Adams Earley," National Museum of the U.S. Army thenmusa.org (accessed June 29, 2023). 2. "Fort Gregg-Adams Redesignation," home.army.mil (accessed June 29, 2023). |

WAC HISTORY - YOUR STORY

Were you or someone you know a member of the Women's Army Corps (WAC)? Visit the following websites and learn how to tell the story of your service via oral history, photos, official and personal records, and memorabilia.

United States Army Women's Museum

Fort Gregg-Adams, Virginia (formerly Fort Lee, Virginia)

awm.army.mil

Women in Military Service for America Memorial

Washington, D.C.

www.womensmemorial.org

The Betty H. Carter Women Veterans Historical Project

University of North Carolina at Greensboro

libcdm1.uncg.edu/cdm/landingpage/collection/WVHP

Were you or someone you know a member of the Women's Army Corps (WAC)? Visit the following websites and learn how to tell the story of your service via oral history, photos, official and personal records, and memorabilia.

United States Army Women's Museum

Fort Gregg-Adams, Virginia (formerly Fort Lee, Virginia)

awm.army.mil

Women in Military Service for America Memorial

Washington, D.C.

www.womensmemorial.org

The Betty H. Carter Women Veterans Historical Project

University of North Carolina at Greensboro

libcdm1.uncg.edu/cdm/landingpage/collection/WVHP