Not until July 1, 1943, when President Franklin Roosevelt signed a compromise bill passed by the U.S. Congress to establish the Women’s Army Corps (WAC) giving women full military status.

All true, but... As the historian Mattie E. Treadwell explained in The Women’s Army Corps, members of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) did not receive the same pay, rank, or benefits as male soldiers—a major problem since women in the Marines and the Navy were integrated. The U.S. Congress did take the daring step in 1901 to create the Army Nurse Corps “with somewhat the same status as the later Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps.” Congress did not see fit, however, to grant “full military rank to [Army] nurses until 1944, a year after the WAAC ceased to exist and women were legally admitted to full Army status and rank as the Women’s Army Corps (WAC).” What about the “Hello Girls” who deployed with the Signal Corps in World War I believing they were in the Army? The women returned home to the astonishing discovery they most certainly were not. And the civilian WASPs of World War II? The war ended without Congressional approval for their integration into the Army. Veteran status for the “Hello Girls” and the WASPS was not granted until 1977.

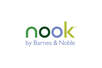

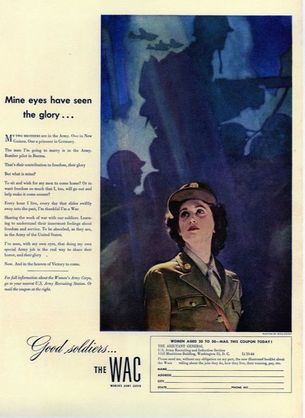

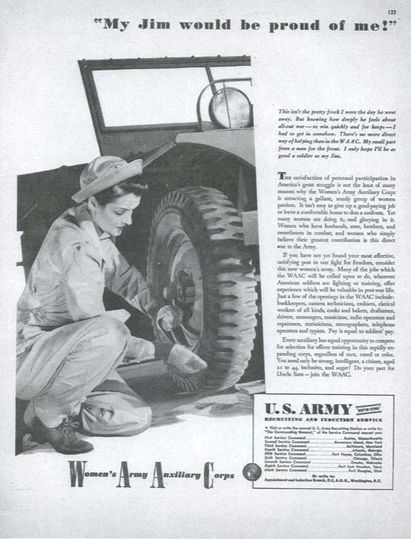

WAC Recruiting Ad - Life magazine, 1944 WAC Recruiting Ad - Life magazine, 1944 In 1931, the “new Chief of Staff, General Douglas MacArthur, overrode a favorable G-1 opinion and informed the Secretary of War that he considered the director’s duties to be of ‘no military value.’” Major Hughes. Meanwhile, in 1928 the Army appointed Major Everett S. Hughes as the chief Army planner for a women’s service corps. The practical Hughes plan--created in 1928 and revised in 1930--likewise recommended a women's corps in the Army. Major Hughes focused on the psychological and managerial aspects of incorporating vast numbers of women into the men’s house of the Army. He emphasized that prior to an outbreak of a war, male decision makers must be trained in understanding the problems of the militarization of women, and females who would help the men make the decisions must be trained in how the Army thinks.

Mattie Treadwell goes on to write,

Auxiliary. U.S. Army planning for a women’s service corps stalled until the war in Europe began in 1939. The new planners seemed unaware of the worthy efforts of Miss Phipps and Major Hughes, but they did agree women would not be given full military status in the Army. Indeed, opposition in the Army and in Congress ran so strong against the notion of women in the Army that Congresswoman Edith Nourse Rogers revised her original intention, and in May 1941 introduced a bill in the U.S. House of Representatives to establish a Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps rather than a Women’s Army Corps. That word auxiliary… Auxiliary meant the women were not in the Army at all. Women in the WAAC did not enlist, they either enrolled or were appointed. WAACs were simply a group of women working alongside soldiers—a situation the Army’s Judge Advocate General “feared—all to accurately as it later proved—legal complication in an auxiliary.” World War II triggers action. The United States entry into the war in December 1941 spurred consideration of the contributions women might make. Amid great controversy, the U.S. Senate approved Mrs. Rogers’ bill on May 14, 1942, to establish the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps. President Roosevelt signed it the following day, and a whirlwind of activity ensued to implement what the new law permitted. The success of the WAAC could not quell the negative attitudes of the male soldiers, family members, and Americans-at-large who not only refused to accept the notion of a female soldier, but also maligned the members of the WAAC. The "Slander Campaign." What came to be known as the "Slander Campaign" exploded with such virulence that in June 1943

The resulting report concluded that the despicable rumors concerning

The WAC: legal for the duration plus six months. Although many Americans opposed adamantly the notion of women soldiers, Congresswoman Edith Nourse Rogers rallied those who did see the need for change. Her amended compromise bill survived the Congressional gauntlet, and on July 1, 1943, the Women’s Army Corps was established

The Act that created the Women’s Army Corps in 1943 also repealed the legislation for the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps. WAAC personnel had to choose either honorable discharge from the WAAC or immediate enlistment in the Women’s Army Corps. No one knew how many women would choose discharge. Ultimately, more than 75 percent of the enrolled WAACs chose to enlist in the WAC. What the legislation establishing first the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps and then the Women’s Army Corps could not do was guarantee the acceptance of women soldiers by the men of the Army. Why it took so long for women to become legal soldiers in the U.S. Army. Mattie Treadwell emphasized that the foot dragging and heated debate about the entry of women into the Army boiled down to what Army psychiatrists later noted,

The women of the WAAC and the WAC served admirably to help win World War II. The women also shared two other major battles: survival and acceptance in the role they chose to carry out. The fight for equality would have to wait. __________ Notes: "Women in the U.S. Army: When did it become legal for women to be soldiers?" compiled by Lynne Schall from the following sources.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorLynne Schall is the author of three novels: Women's Company - The Minerva Girls (2016), Cloud County Persuasion (2018), and Cloud County Harvest (November 2022). She and her family live in Kansas, USA, where she is writing her fourth novel, Book 3 in the Cloud County trilogy. Archives

October 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed