|

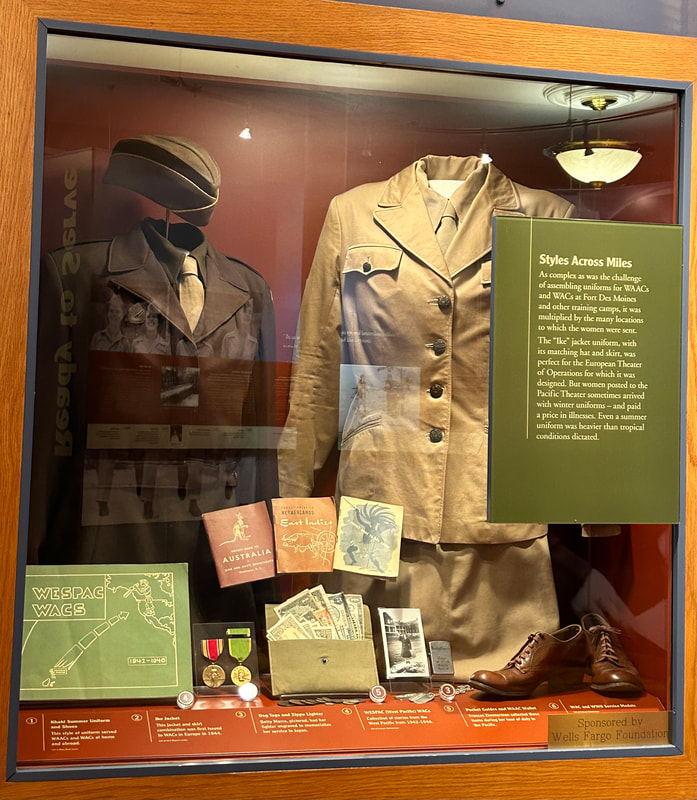

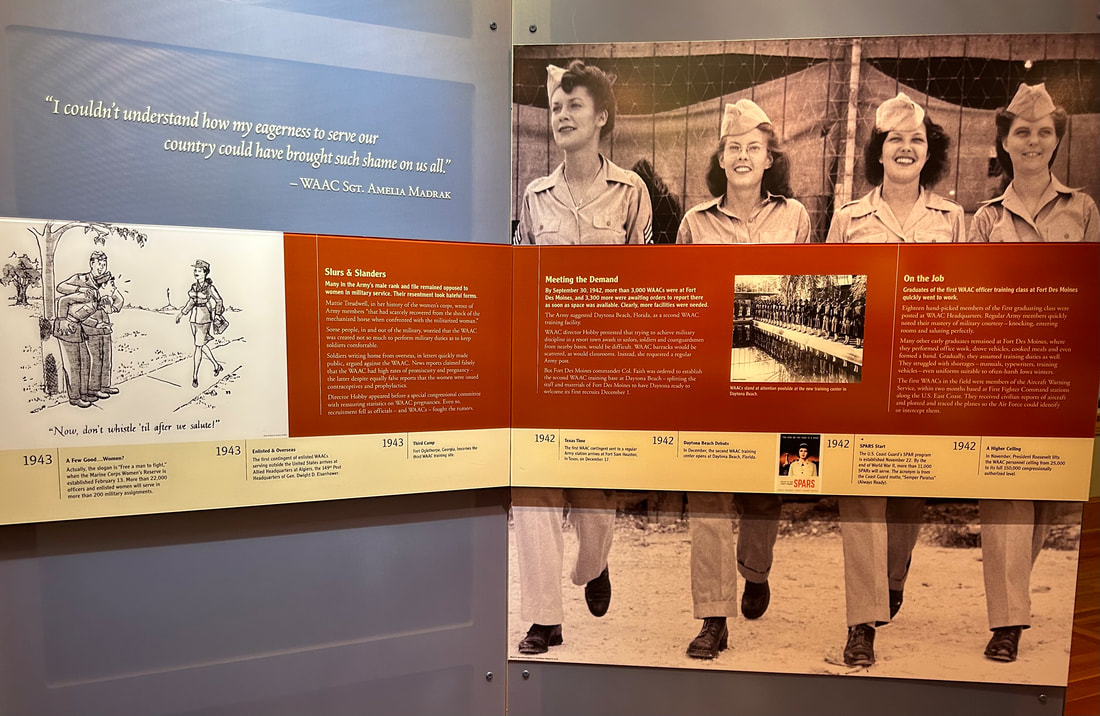

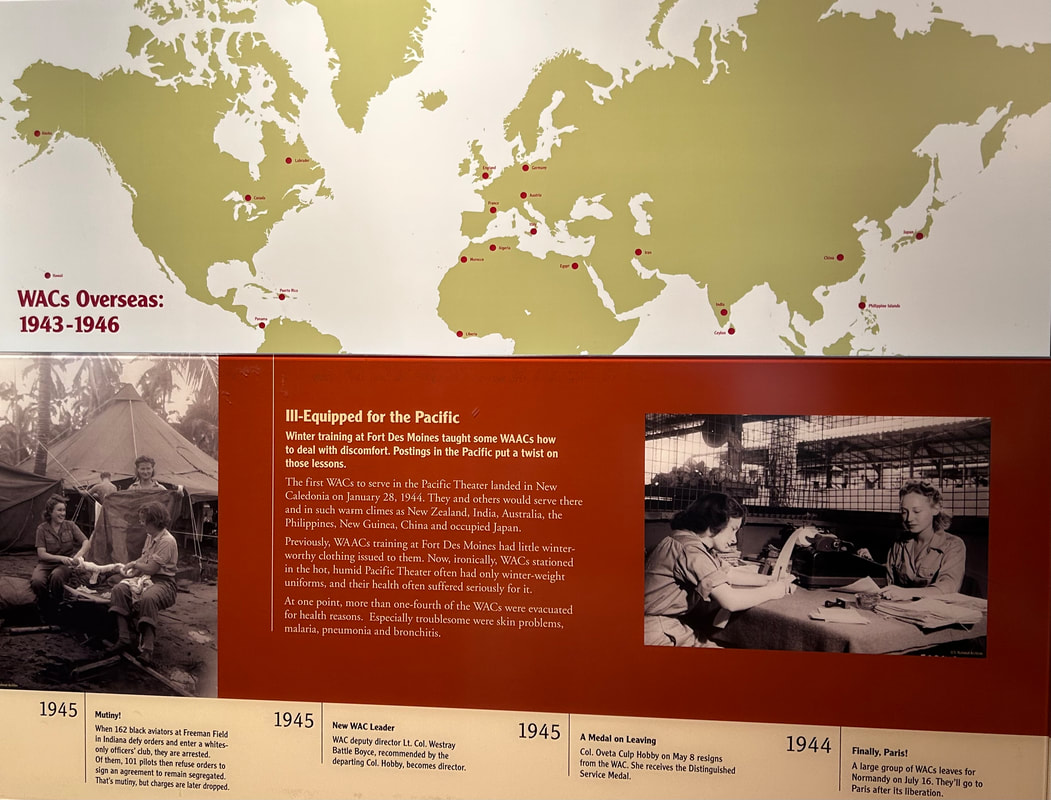

It was 1942, and the world was at war. The December 1941 entry of the United States into what later became known as World War II made everything in America more intense if not always faster. The frantic need for success in a nation unprepared for war often goaded the U.S. Congress to do what it previously would not. On May 14, 1942, Congress approved the establishment of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corp (WAAC). The following day, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the bill into law. On May 16, Oveta Culp Hobby was sworn in as the first director of the WAAC. Little did the people of Iowa know that Fort Des Moines, located on the south side of their capital city, would become the site of the first training center for the newfangled WAAC. The whole nation was watching. The Need for More “Manpower” Recruiting and training women became an immediate and continuous goal of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC). That goal continued when the WAAC converted to the Women’s Army Corps on July 1, 1943. In those early months of recruiting, some 30,000 women filed applications to compete for less than 1,000 positions. The WAAC picked the best and made plans to expand as necessary. By the end of World War II, over 150,000 women had served in the WAAC/WAC. Hold Your Horses No training could begin without a training center. For a few crazy weeks, the search proved fruitless. Brother and sister arms already had dibs on potential space at large colleges, universities, private and public schools, resort hotels, state fairgrounds—anywhere that might be adapted to the WAAC’s use. Moreover, the WAAC could neither sign a legal contract for space nor begin conversions to that space until after Congress’s bill became law. Fortune smiled on the WAAC in late April 1942 when the mechanization of the U.S. Calvary made available an old, mounted Calvary post: Fort Des Moines, Iowa. Fort Des Moines sat halfway across the nation from WAAC headquarters. Cold, snowy Iowa winters would challenge an overstretched Army clothing supply chain. Brick stables for horses would have to be converted to barracks for women. Additional construction would be necessary. However, solid red brick barracks surrounded a huge, green parade ground. The fort's utilities could be expanded to accommodate 5,000 people. The area didn’t have large defense projects or race and color difficulties. “We’ll take it!” the WAAC planners agreed. Fierce resistance to women in the Army—even as auxiliaries who were only with the Army, not in it—plagued the WAAC and later the WAC. And to the detriment of everyone, intractable racial discrimination wounded the United States. Yet, Des Moines possessed a strong African-American community.

First WAAC Officer Candidate Class The historic first WAAC officer candidate course trained 440 WAACs and took place from July 20 to August 29, 1942. The women’s course was shorter in duration than the men’s because the ineligibility of women for combat eliminated the need for combat subjects. The forty black women who entered the first WAAC officer candidate class were placed in a separate platoon. Although they attended classes and mess with the other officer candidates, post facilities such as service clubs, theaters, and beauty shops were segregated. Black officer candidates had backgrounds similar to those of white officer candidates. Almost 80 percent had attended college, and the majority had work experience as teachers and office workers.” The strained supply chain of wartime could not provide everything the candidates needed, but morale and public interest ran high. Reporters, photographers, and dignitaries popped up, whether or not they were invited. They couldn’t always get into Fort Des Moines, but anyone could watch new recruits getting off the trains in Des Moines, and later, WAACs walking about downtown during their limited free time. Did the WAACs establish additional training centers? The U.S. Congress authorized a maximum strength of 150,000 for the WAAC. When job classification experts pointed out that a modern army offers far more jobs suitable for women, Army estimates for women volunteers jumped to 1.5 million. Army planners floated the idea among themselves of seeking Congressional legislation to draft women. The likely public and Congressional opposition to such a radical notion nixed that idea. Whether the Army needed a 150,000 or a million WAACs, Fort Des Moines couldn't train them all. Ultimately, and sometimes briefly, the Army conducted five WAAC training centers. All but Fort Des Moines were located east of the Mississippi River. All five training centers were created before the WAAC was disestablished on September 30, 1943. The centers bore practical names in numerical order: the First WAAC Training Center, the Second WAAC Training Center, etc. In addition to the training centers, separate specialist schools were created. On September 1, 1943, the Army redesignated all WAAC units as WAC.

At first we were frantic because we didn't have enough cadre to take care of the trainees, and now we didn't know what to do with the cadre. By March of 1944 only the First and Third Training Centers continued in operation. The Second WAAC Training Center ran from October 1942 to not later than early 1944. Surprisingly, the unlikely location of Daytona Beach, Florida (yes, that Daytona Beach) was selected. No Army post existed there, so the women lived and trained in a hodgepodge of civilian buildings leased throughout the resort town. A tent camp expanded the women's barracks. The Fourth WAAC Training Center operated for six months (March 1943 – August 1943) until discussion of a possible draft for women was scrapped. The Fifth WAAC Training Center lasted only three months (April 1943 - June 1943) due to the need for housing Italian prisoners-of-war captured in North Africa. No matter where WAACs, and later WACs trained, it wasn't long before they were on the job--but not always in their respective areas of civilian expertise or Army specialist training. Most women were stationed in the United States, others were deployed around the world. What is Fort Des Moines like today? As the needs of the Army changed in the second half of the twentieth century, the military eventually turned over Fort Des Moines acreage to the City of Des Moines for development by public and private entities. Many of the fort’s buildings were demolished. The oldest surviving structures of Fort Des Moines Number 3 are Clayton Hall and the Chapel. (Two previous Army posts named Des Moines were established and abandoned in the nineteenth century.) Clayton Hall and the Chapel have played many roles since their respective creations in 1903 and 1910. The two “grande dames” remain on their original site. Today, they compose the Fort Des Moines Museum and Education Center. MISSION of the Fort Des Moines Museum and Education Center: preserve, promote and perpetuate the sacrifice, service, and leadership of the Black Officers of World War I, the Women’s Army Corp (WAC) of World War II, and all others whose lives have been connected to Fort Des Moines. The museum packs a great deal of history into its informative and easy-to-understand static displays. I thoroughly enjoyed my visit to Fort Des Moines in September 2023. Currently, the museum is open only on Saturdays and by appointment. The building’s exterior requires some repair, as does the monument and empty reflecting pool facing Clayton Hall. Visit the museum’s website https://www.fortdesmoinesmuseum.com to learn more about its partners, volunteers, and events. Better yet, see the “grande dames” in person and learn how you can support their work! __________

Notes: 1. Lynne Schall's color snapshots of displays at the Fort Des Moines Museum and Education Center, September 2023. 2. "Boomtown," black and white snapshot, Betty H. Carter Women Veterans Historical Project, University of North Carolina at Greensboro. 3. Mattie E. Treadwell, Lieutenant Colonel, U.S. Army, The Women's Army Corps, Special Studies, The U.S. Army in World War II, Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army, Washington, D.C., 1954, 1995. 4. Judith A. Bellafaire, The Women's Army Corps: A Commemoration of World War II Service, CMH Publication: 72-15.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorLynne Schall is the author of three novels: Women's Company - The Minerva Girls (2016), Cloud County Persuasion (2018), and Cloud County Harvest (November 2022). She and her family live in Kansas, USA, where she is writing her fourth novel, Book 3 in the Cloud County trilogy. Archives

October 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed