|

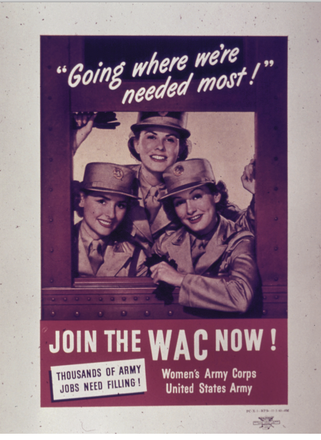

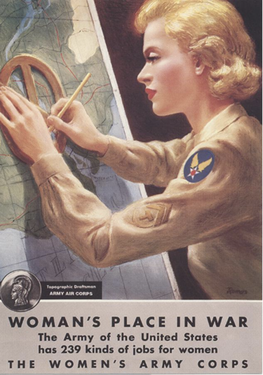

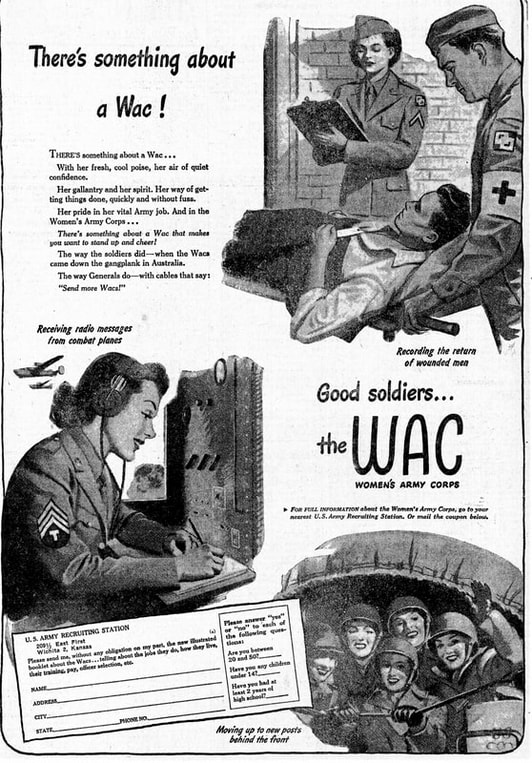

Advertising is a perennial repository of culture. Consider the advertisements used by the U.S. Army to recruit women during World War II. You’ll find a wealth of hints regarding not only the culture of the Army, but also the American public. As you look at the ads I’ve selected, ask yourself, “Who’s in the ad? Who’s left out? Are they depicted in an accurate or idealized fashion? Why or why not?”

Army jobs assigned to women still required candidates who already possessed training and experience, or who could learn it quickly. Given the competition for workers, the WAAC—under duress and against its good judgment—lowered the minimum entry requirements for a scant few months. The results were unfavorable. Restoring the original enrollment standards on April 7, 1943, resolved the issue. In May 1943, statistical records showed Waacs still surpassed in qualifications both the civilian average and that of Army men. The ‘average’ Waac at this time was a mature woman, 25 to 27 years old, healthy, single, and without dependents. She was a high school graduate with some clerical experience….The WAAC rate of venereal disease was almost zero…the pregnancy rate among unmarried women was about one-fifth that among women in civilian life.” --Mattie E. Treadwell, The Women's Army Corps. Facts, however, did not stop a “slander campaign.” Treadwell described a firestorm of gossip, jokes, slander, and obscenity about the WAAC sweeping across the country in the spring of 1943. What had started as a “whispering campaign” exploded just after Army leaders emphasized the need for thousands more women in uniform in exchange for more men on the fighting front. The storm lasted well into the next year. Although partially subdued, it did not burn out.

Would the new Women's Army Corps survive? No one knew for sure. Especially since normal attrition overtook recruiting accessions during the 90-day conversion period. Fortunately, more than 75 percent of the approximately 60,000 Waacs did join the Women’s Army Corps. Which Waacs stayed to sign up with the new WAC? The ones who were wanted and needed on their jobs. The hostility of many Army men toward Waacs, together with the poor opinion of Waacs held by much of the American public, took its toll. Patriotism would still play a part in recruiting but, according to Treadwell, the new drive would emphasize, first, the hundreds of types of Army work now open to Wacs, and second, WAC benefits, which now offered the greater advantage of full military status.”

…glamorization was also deemed essential, at different times, by both British and WAVES recruiters, in both cases over the objections of women directors.” --Mattie E. Treadwell, The Women's Army Corps. The Six Triple Eight. Women of color served in the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps and the Women’s Army Corps from the start. Perhaps the most well-known story about them in World War II is the 6888th Central Postal Battalion, the only all-black, all-female Army battalion to serve overseas during World War II. Charity Adams Earley, commanding officer of the “Six Triple Eight,” chronicled their story in her excellent memoir, One Woman’s Army: A Black Officer Remembers the WAC. Who is in the recruiting ads? Not nurses or doctors, because by act of Congress the WAC was forbidden from those roles. Women in the WAC ads are portrayed as young, attractive, well-groomed and—whether dressed in uniforms with skirts or trousers--feminine. In short, the type of women with whom parents, siblings, sweethearts, and husbands would not mind their loved ones associating. Every ad that I have seen for the Auxiliary and the WAC of World War II features white women. The only sizable racial minority group in the WAC was that of the Negro, although a few women of Puerto Rican, Chinese, Japanese, and American Indian descent were also enlisted. Members of most of these groups, except the Negro, were very rarely recruited, and were not segregated, but scattered through ordinary WAC units according to skills…. Who researched and developed the recruiting material for print, radio, and film? It took time for the Army to realize that, in the absence of a draft for women, it had to engage the most highly qualified publicity experts and retain central control of both paid and free advertising. Treadwell indicated that estimates of the “value of free sponsored advertising obtained by the WAC in the last nine months of 1944 exceeded $15,000,000.” Not only members of the Army with publicity, sales, and recruiting expertise, but also professional advertising agencies such as N.W. Ayer & Son and Young & Rubicam worked to determine the most effective way to recruit women. Given the prevailing attitudes about appropriate male and female roles, the U.S. Congress had already mandated a voluntary status for women. Most importantly, women would not train for combat, would not fight on the battlefield, and would never—unless specifically ordered to do so by Army superiors—command men. Advertising had to convince eligible women to voluntarily trade the familiarity of their civilian lives for the unfamiliar and masculine world of the military at a time when the American economy clamored for women workers. What did the ads say? The text in the ads declares the normalcy of a woman’s place in the Army, the usefulness of her work, and the variety of jobs available to her. She enjoys Army life, and her loved ones are proud of her service. Men were drafted. Why weren’t women? The Army considered drafting women during the manpower crisis of 1942. The Army’s General Staff rejected the proposal as impossible. The red-hot competition for qualified women compelled the revival of the women’s draft question in 1943. Gallop polls showed that 73 percent [of Americans] in October of 1943 and 78 percent in December believed that single women should be drafted before any more fathers were taken. Single women of draft age themselves endorsed their draft by a 75 percent majority, although stating that they would not voluntarily enlist so long as the Government did not believe the matter important enough to warrant a draft.” --Mattie E. Treadwell, The Women's Army Corps. However, the U.S. Congress was not thinking along those lines at the moment. The Army’s General Staff decided the more productive strategy would be to support national service legislation when some other entity sponsored it. The January 1944 announcement by the War Department that approximately six million men still in training stations must be shipped overseas by the end of the year, sparked serious consideration by Congress of the pending Austin-Wadsworth bill for “civilian selective service.” The American Federation of Labor opposed the bill. So did the Congress of Industrial Organizations. Then the U.S. Senate’s Truman Committee opposed the idea, and the bill was dropped. Without legislation to direct women into either the armed forces or industry, the competition for womenpower increased beyond the earlier “manpower” crises of 1942 and 1943. Apparently, the United States would have had to experience an even longer war and/or suffer great reverses on the battlefield in order to legislate a military draft of women or a civilian selective service. Did the Women’s Army Corps ever meet its recruiting goals? No. Approximately 16 million people served in the armed forces of the United States during World War II. More than 400,000 of the 16 million were women. And of those 400,000 women, more than 150,000 served in the WAC. Female soldiers proved their worth to the mission of the Army and won positive recognition by leaders in and out of the military. Nonetheless, negative mindsets persisted. By early 1944, WAC recruiters had identified the greatest obstacle to recruiting volunteers: the general public’s often low regard of women in the armed forces—an opinion traced frequently to the opposition by men in the Army. Recruiters also noticed that male soldiers who actually met and worked with Wacs often accepted—and sometimes married--women in the Army. Not surprisingly, advocates of military women doubled-down in their efforts to meet the needs of a nation at war. The U.S. Congress created the Women’s Army Corps for the duration of the war plus six months, and then directed the Army to achieve a temporary shift of public opinion in order to ensure the WAC’s success. Although the Corps never reached suggested recruiting goals, it made a defining step toward the expansion of the role of women in American culture. __________

Notes: "What Can Women's Army Corps Ads Tell You About the U.S. in WWII?" compiled by Lynne Schall from the following sources: 1. Bettie J. Morden, The Women’s Army Corps, 1945-1978, Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, United States Army, Washington, D.C., 1990, 1992. 2. Mattie E. Treadwell, The Women’s Army Corps, Special Studies, The U.S. Army in World War II, Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army, Washington, D.C., 1954. 3. U.S. National Archives.

4. U.S. National Archives, Online Exhibits, Powers of Persuasion.

5. Women in Military Service for America Memorial, Press Resources, “Highlights of Women in the Military,” http://www.womensmemorial.org (accessed April 30, 2019). 6. Women of World War II, World War II Recruiting Posters, http://www.womenofwwii.com (accessed April 30, 2019)

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorLynne Schall is the author of three novels: Women's Company - The Minerva Girls (2016), Cloud County Persuasion (2018), and Cloud County Harvest (November 2022). She and her family live in Kansas, USA, where she is writing her fourth novel, Book 3 in the Cloud County trilogy. Archives

October 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed